Over the past few months, I’ve been learning quite a bit about virtual filesystems, so I thought I’d share the knowledge in the form of a tutorial post.

This tutorial is aimed at an intermediate level, as it uses a number of high-level python features and libraries, as well as dealing with the confusing topic of filesystems. However, it should still be understandable for beginners, if you’re willing to do some googling while reading. I will assume that you are using a linux system, as that is the system that FUSE is built for.

What is a filesystem?

According to Wikipedia, a filesystem is a piece of software that “controls how data is stored and retrieved” on a physical storage medium. As you probably know, your main disk is split up into multiple partitions - each of these partitions will generally have a single filesystem on it, so that programs can read and write to it.

The point of filesystems is that while they may work differently under the hood, they all present the same interface. This means that you, as a user or programmer, are not aware of any of the underlying details of what is actually happening. You can just create, read and write files, and create directory structures without worrying about how it will be stored on disk.

There are lots of different types of filesystem that can be installed on partitions, including NTFS (typically used by Windows) and ext4 (typically used by Linux).

All of these filesystem drivers are implemented in kernel-space, which means that adding them or modifying them requires fairly heavy amounts of work, probably involving compiling the kernel yourself, and lots of low level fiddling. So what happens if you want to create a custom filesystem for, say, a mobile phone that you attach and communicate with over MTP? This is too specific a case for a kernel driver, but it’s definitely a valid use case.

Introducing FUSE…

What is FUSE?

FUSE stands for Filesystem in Userspace. Yes, it’s a weird acronym.

What FUSE lets us do is create filesystems as a normal user. Whereas the filesystems discussed above are implemented in kernelspace, FUSE lets us do it in userspace, without having to write a whole filesystem driver. It wraps all filesystem calls from its mountpoint and sends them to a program, which can then decide what to do with them. This allows us to make things that look a lot like and act a lot like files, but are actually calls to a program.

Now, while it is comparatively easier to build a FUSE filesystem, it can stil be fairly involved, so we’re going to build it using MagicFS (disclaimer, yes I built it). MagicFS is a wrapper library over FUSE which provides a simple handler interface and a few utility functions so we don’t have to worry about all the low level details.

Building our own filesystem

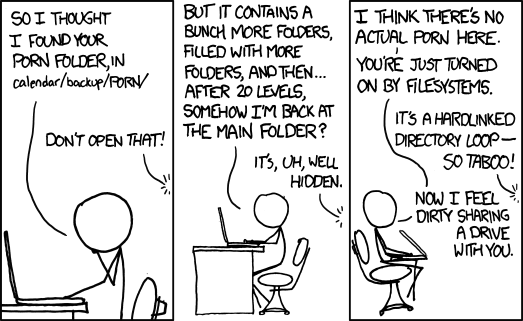

Before we do anything, we need to work out what exactly we are going to be making. FUSE filesystems are quite good at doing things that are bizarre and strange, so we should probably pick something that shows off that ability.

xkcd is a source of entertainment for lots of software engineers, so, in the spirit of the comic and wasting time making something that doesn’t really need to exist, we’re going to make xkcdfs, a filesystem for browsing xkcd comics.

Setup

Let’s set up our environment. We’re going to be using python3, so make sure that you’ve got it installed and setup (which should be the default on most modern linuxes). You also need to have FUSE itself, which will be different for every linux distro.

Finall, we install MagicFS itself (which is also known as mafs in some places for brevity).

$ pip install mafs

Now, we can start creating our program. I recommend doing it in a seperate directory so we can make a bit of a mess.

$ mkdir xkcdfs

$ cd xkcdfs

Now we can start writing code! To test that we’ve got everything setup properly we can run the following code which simply creates a virtual file at “/hello” that contains the content “Hello, World!”.

# main.py

import mafs

fs = mafs.MagicFS()

@fs.read('/hello')

def hello_world(path, ps):

return 'Hello, World!'

fs.run()

To run it, we create the directory to host the filesystem in.

$ mkdir fs

Then we can mount our filesystem by running our program (with the option -fg

to run it in the foreground, which is useful for debugging and stopping it).

$ python main.py fs -fg

Now if we have a look around (from another terminal, or even a file browser):

$ tree

fs

└── hello

0 directories, 1 file

$ cat fs/hello

Hello, World!

When we’re done, just quit the program with CTRL+C.

Writing code

Now that everything’s setup properly, we can actually start writing some code. If you’re interested in the finished product, you can see it here.

Before we go any further, let’s set up our basic layout.

# main.py

# our main library

import mafs

# used to create file-like objects

from io import BytesIO

# used to get and parse data from xkcd.com

import urllib.request

import urllib.error

import json

# create our filesystem

fs = mafs.MagicFS()

# the rest of our code goes here...

# mount and run the filesystem with reasonable defaults

fs.run()

First off, let’s write a couple of utility methods to get our data from xkcd.com.

comic_cache = {}

def get_comic(comic=None):

# download comic data if not already stored

if comic not in comic_cache:

# calculate url, with default being the latest comic

if comic:

url = 'http://xkcd.com/' + str(comic) + '/info.0.json'

else:

url = 'http://xkcd.com/info.0.json'

# download comic data

try:

response = urllib.request.urlopen(url)

comic_cache[comic] = json.loads(response.read())

except urllib.error.HTTPError:

return None

# get cached comic data

return comic_cache[comic]

image_cache = {}

def get_image(url):

# download image if not already stored

if url not in image_cache:

response = urllib.request.urlopen(url)

image_cache[url] = response.read()

# return file-like interface for image data

return io.BytesIO(image_cache[url])

Now that we can get data from the site, we can start to think about the structure of our filesystem. We’ll have all the numbered comics as file names, running from 1 to (at the time of writing) 2083.

Let’s write our code to read the images in.

@fs.read('/:number', encoding=None)

def read_comic(path, ps):

data = get_comic(ps.number)

if data:

picture = get_image(data['img'])

return picture

We declare a handler under the root with the variable parameter number. This

is a parameter whose specific value can then be accessed using ps.number. At

the end of the function, we return a file-like object. Note that we have to

explicitly set the encoding as None to indicate that the data should be

treated as binary data.

We can give this a quick test by running our code, and then opening one of the files as in an image viewer. You will need to start the image viewer from the command line, giving the filename as a parameter. For example,

$ feh fs/1513

Hopefully, you should see a comic. If you can’t, make sure that you have got everything installed and configured correctly and that you have followed the instructions properly.

Unfortunately, while the files exist, and we can view the files in an image

viewer, we can’t see any files in our directory using ls or a file viewer.

MagicFS can pick up on simpler directory structures, like the Hello World

example, but it can’t automatically do so with variable parameters.

So, let’s make sure that they appear!

latest = get_comic()

@fs.list('/')

def list_comics(path, ps):

return (str(i) for i in range(1, latest['num'] + 1))

@fs.stat('/:number')

def access_comic(path, ps):

try:

if int(ps.number) > latest['num']:

raise FileNotFoundError()

except ValueError:

pass

As you can see, this requires two methods to be created - firstly, a @list method and secondly, a @stat method. Both of these are required, because as we start taking manual control of the filesystem away from MagicFS using @list, we need to provide it with enough information about the file so that it can operate on it properly.

We can now run our program, and see that we can see all our files and have access to them. To view the entire source code see here.

Conclusion

Now we have our very own virtual filesystem! It’s lot of fun to mess around with, and if you’re interested in it, please check out MagicFS a bit more. I’d love to have some more users (and possibly even some contributors!). If you want something a bit more low-level, look into libfuse, the official library for programs interfacing with FUSE.

Hopefully, this has been easy enough to follow along with. If not, please reach out to me at the email address on my Github profile - I’d love to hear your feedback.

Until next time.